Valley Cemetery and Mar's Wark Garden

Growing population would have forced larger Scots towns to adopt new burial systems around the mid nineteenth century even without new ideas of what was appropriate and hygienic. By the 1850s, the Holy Rude Kirkyard was so overcrowded that older graves were regularly disturbed to make way for new burials; access to almost every plot involved trampling over others.

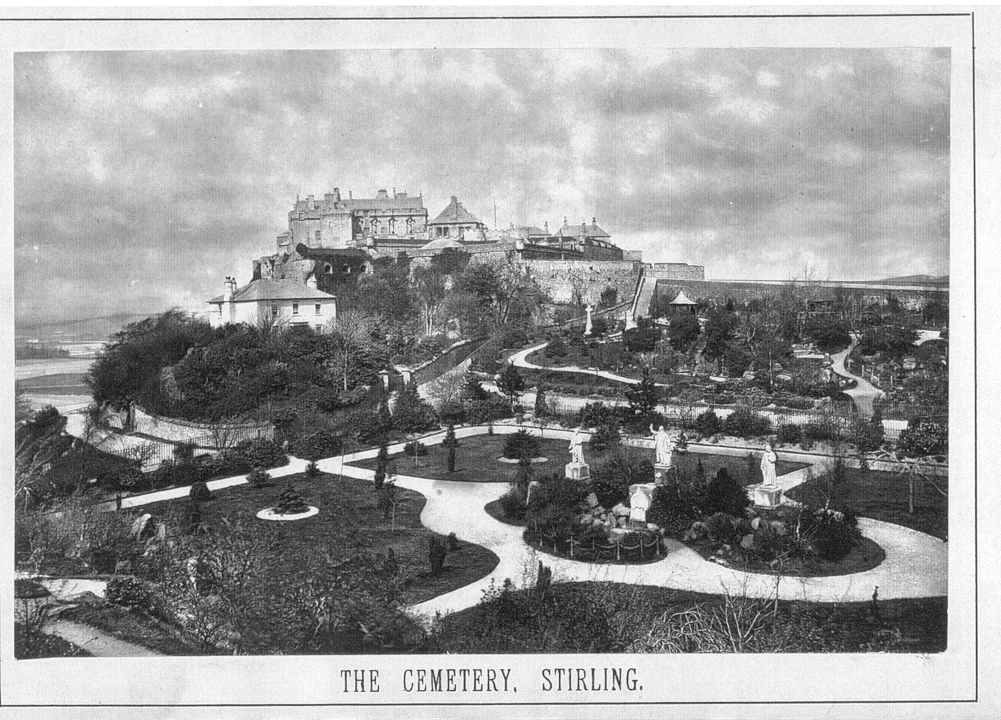

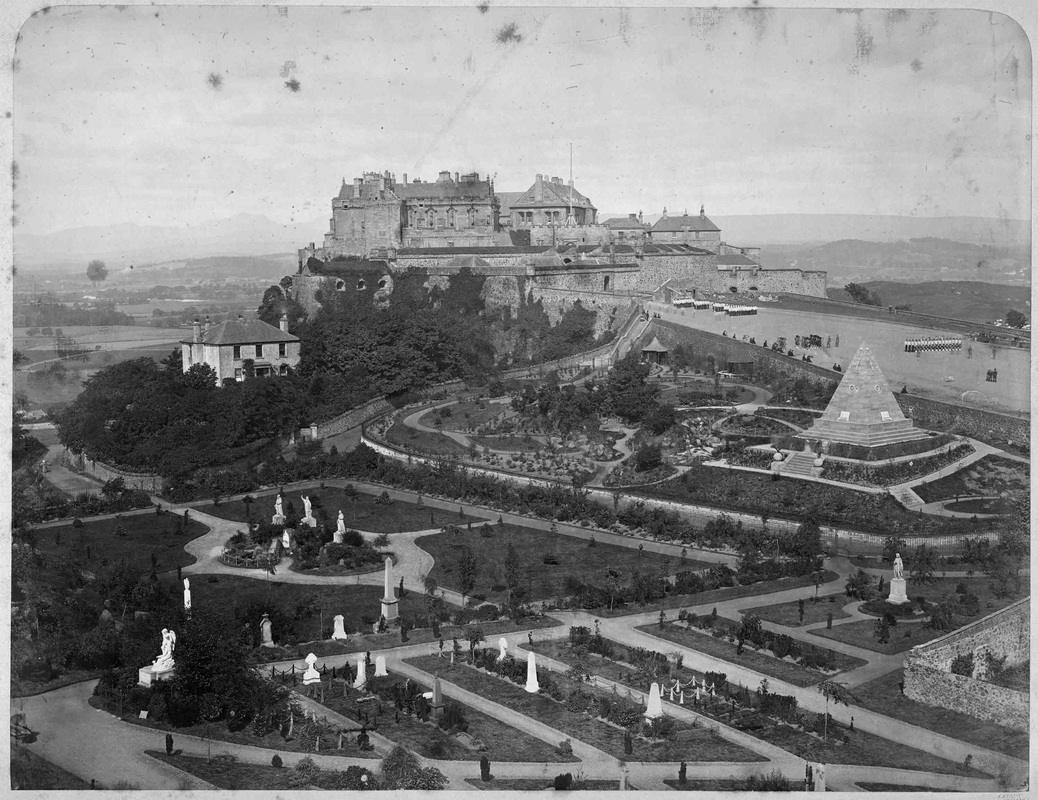

The Valley Cemetery was opened in 1857-8 and was quickly extended into the adjacent Mar’s Wark Garden. It gave carriage access to every plot. Each grave was to be used only once. And the whole area was designed to be ornamental and attractive,

in a style known as ‘gardenesque’ and characterised by copious planting of trees, by enclosure from the surrounding world and by statuary, pools and other features found in fashionable gardens of the period.

The Stirling design served other purposes beside burial. The paths linked to the castle and to the main tourist walkways round the town, such as the old Back Walk. And the statues of Presbyterian heroes and heroines added an ‘educational’ and ‘improving’ dimension. This was recognition that numbers of tourists were growing following the arrival of the railway in 1849. For most of these visitors the castle was the main object of interest but there was a clear need to provide other things for them to do. For a time there were even cemetery guides to explain the main points of interest.

The Valley Rock Fountain supplied drinking water. But this was also intended to be symbolic or ‘spiritual’ water to refresh the soul as well as the body. Consistent with the overall message of the Valley, it springs from the feet of three key Presbyterian teachers. These statues, like the others, were sponsored by ardent local Presbyterians, particularly William Drummond.

The Valley Cemetery was opened in 1857-8 and was quickly extended into the adjacent Mar’s Wark Garden. It gave carriage access to every plot. Each grave was to be used only once. And the whole area was designed to be ornamental and attractive,

in a style known as ‘gardenesque’ and characterised by copious planting of trees, by enclosure from the surrounding world and by statuary, pools and other features found in fashionable gardens of the period.

The Stirling design served other purposes beside burial. The paths linked to the castle and to the main tourist walkways round the town, such as the old Back Walk. And the statues of Presbyterian heroes and heroines added an ‘educational’ and ‘improving’ dimension. This was recognition that numbers of tourists were growing following the arrival of the railway in 1849. For most of these visitors the castle was the main object of interest but there was a clear need to provide other things for them to do. For a time there were even cemetery guides to explain the main points of interest.

The Valley Rock Fountain supplied drinking water. But this was also intended to be symbolic or ‘spiritual’ water to refresh the soul as well as the body. Consistent with the overall message of the Valley, it springs from the feet of three key Presbyterian teachers. These statues, like the others, were sponsored by ardent local Presbyterians, particularly William Drummond.

|

|

The Star Pyramid or Salem Rock was dedicated in 1863. The pyramid form was popular and symbolised stability and endurance. The inscriptions refer to key aspects of the development of the Presbyterian Churches in Scotland. The surrounding area, now called Pithy Mary, was then known as the Drummond Pleasure Ground from William Drummond who paid

for the pyramid as well as the statues and who is buried beside it. For a brief review of the Valley Cemetery, its symbolism and setting see John G Harrison, 2010. ‘The Kirkyard and Cemeteries beside Stirling Castle’, Forth Naturalist and Historian, volume 33, 49-59. See more on Valley Cemetery Gravestones |